What's inside a stone circle?

We begin with flint, travel through time a bit, consider stone circles, Derek Jarman, and the New Folklore movement, before ending up back at flint. What is it that attracts you to a thing?

I'm going to build a stone circle out of flint.

//

Flint is everywhere in Norfolk. Walk past any freshly ploughed field and you will see it, shattered and plucked out of the soil by the relentless metal blades. Norfolk Churches and other old buildings are often coated in flint. Intact stones are patterned into pretty, multicoloured courses and herringbone, whilst knapped blocks form hewn black scales. Flint also makes a good cobblestone. Smaller rounded pebbles line the surfaces of medieval East Anglian village market-houses and narrow, uneven town byways.

As well as a building material, flint has been used across human history for two most significant purposes: stone tools and starting fires. It is a rock that defined the Stone Age, technologically augmenting human abilities to hunt and kill other animals; to skin and butcher for food and fur; to fell trees and shape wood into shelter and other tools; and to voluntarily start fires which offered warmth, safety, and a hearth to gather around and form community.

In the Lower Paleolithic Oldowan period the main source material for stone tools were river cobbles. By the Neolithic period humans had become miners, digging deep into the ground to find the rocks that best suited their purpose and imagination.

One place they dug particularly deep and over centuries of time is Grime's Graves, in South East Norfolk.

Descending the metal stairs into Pit One, visitors simultaneously pass through tens of millions of years of geological time and thousands of years of human time, until they reach the third layer of flint — 'the floorstone', the flawless, glossy black rock that took so well to knapping and seemed to be revered by those who dug for it. 90 million years ago and 4600 years ago converge.

Time can be measured horizontally at Grime's Graves as well. Each dip in the ground represents one mine shaft, worked for some period of time before a closing ritual was held, the shaft filled in, and miners moved on to a new spot. How many summers would be spent on each mine? It surely varied, depending on the number of people who came to carry out seasonal work on the site, the energy available to them, and the amount of good quality flint that could be found, amongst other variables.

Each dip is not a precise measure of time then, but as a whole, the field becomes a monumental geographical calendar. Humans spent hundreds of years at this place digging for rocks that held practical and spiritual value to each of them, and you can see that time laid out on the ground, divided into uneven but comparable circles that represent years of physically and mentally demanding labour.

Surely there were disaffected miners, and there is evidence of children working the pits — but this labour was also undoubtedly unalienated and satisfying. The products of their work were tools for survival and of great beauty. They were revered objects of magical power left as offerings to the Mother, and they were used daily to kill, scrape, and chop.

The eventually disused mines became graves and middens. They were used to dump waste products from metalwork in the Bronze Age, whilst Iron Age locals would bury their dead in them for a few hundred years. Saxons believed the inverted-mounds were clawed out by Grim [Woden], leader of the wild hunt, and gathered nearby to hold moots. Now the site is bordered by military training ground, fences keeping preserved history out of the modernity of the present day.

Flint mined from Grime's Graves has been found in archaelogical sites in the Netherlands, Denmark, France, and Belgium; Poland, Germany, Czechia and Slovakia. Speculative links have been made to Italy and other Mediterannean countries. Neolithic trade networks were vast, and people travelled long distances for trade, cultural exchange, exploration, social interaction, and pilgrimage. Borders and boundaries as we conceptualise them — realities scored deep into the earth's fleshy epidermis and thrust up towards the heavens as sharpened fences, fortified walls, and bureaucratic labyrinths — almost certainly didn't exist.

Flint then, feels like an appropriate material with which to work in this area of the world. It is of this place and contains allusions to a time when modern enclosures were less constricting of the human condition. Stone circles don't pen you in. They are portals to other worlds.

//

My interest in stone circles as sites of affective power goes back to my childhood, but it has been renewed and intensified in recent years by the culture growing around these places.

Groups concerned with Earth Mysteries and other alternative-antiquarian and amateur-academic or psychogeographic readings of these sites have existed for decades. The likes of Northern Earth, Meyn Mamvro, and various Ley Hunting groups survive to this day, and Monica Sjöö and Julian Cope have long been extolling the psychic and revolutionary power of these places. More recently, a thriving contemporary arts scene has emerged around ancient stone circles and other such monolithic and folkloric sites.

Zines, social media pages, small presses and fashion studios such as Stone Club, Weird Walk, Scavenged Rituals, Neolithic Bimbo, HERESY, Fantastic Folk.

Artists and creators are making exciting and beautiful work in response to these sites: Jeremy Deller, Nicolette Clara Iles, Jem Finer and Jimmy Cauty, Rachel Poulton, Daniel & Clara, bones tan jones, Ben Edge, Lucy Stein, Jarvis Cocker, William Arnold, Orbury Common, Mads Washbrook, and Alex of Stone Wizard Tattoos, amongst many more.

My inspiration for the flint circle though comes in large part from someone who's influence on this [New Folklore?] scene looms large despite their sad absence; Derek Jarman.

In the garden at Prospect Cottage there lie a series of circular beds, laid out with pebbles from the Dungeness shingle. These miniature-but-human-scale stone circles offer a home to the plants that grow within their permeable borders, but they also create a ritual landscape upon the ground. The act of laying out these circles, constructing these shapes of power with a material collected from the local environment, was an act of place making not dominating or possessive, but responsive and respectful, a cocreation between location and imagemaker. These circles honour the beach, the artist, and the home. They speak of the connection between the human, Derek Jarman, and the place, Dungeness, that he inhabited - and which inhabited him. They reference other places, other stone circles, where human and nature seem entwined and enmeshed; circles that exist in Eustasian Positions, like Jarman's garden, identified by people who spoke continuously with the world around them and held a deep awareness of and connection with the sublimity and immanence of the universe.

I think these circles look beautiful. I find them conceptually compelling, visually satisfying, and can make the intellectual argument for why I want to reference them with my own creations. These seem sufficient reasons alone to generate the desire to construct flint stone circles in my garden.

But there is another reason that I can think of too. I like Derek Jarman, and I like the people who created the original ancient stone circles too. I feel a connection with these people, a kinship, a sense of simpatico. We might get on. I am drawn and attracted to these people, and their creations provide a vector for the consummation of a relationship, even if distant, parasocial, and one-sided.

What I really like is my own projected imaginations of these now dead people. These projections are informed in large part by the art that they left behind, the marks they made on the land — and therefore there is a reflexive relationship between my love for the art and my love for the people who created the art.

But undoubtedly, I feel an erotic attraction to the things that I do at least partially because I feel an erotic attraction to the people who make these things, or to the people who express their own erotic attraction to such things. I love Derek Jarman, and so I love his work, and I love the work that he loved.

This feels like cheating sometimes; I only like this thing because Person I Like liked it too. Is this shallow? People-pleasing? An invalid reason to be interested or excited about something? Am I outsourcing my decisions about what or who to love to others?

I don't think so.

Rather, it speaks to the way in which I conceptualise objects. Perhaps because of the way my abstract aphantasic mind works, when I think of 'stone circle', I do not picture specific stone circles or my sensory experiences with them. Rather, I am vaguely aware of a trove of references and associations that 'stone circle' touches in my subsconscious realm. With effort, I can bring some of these associations into consciousness.

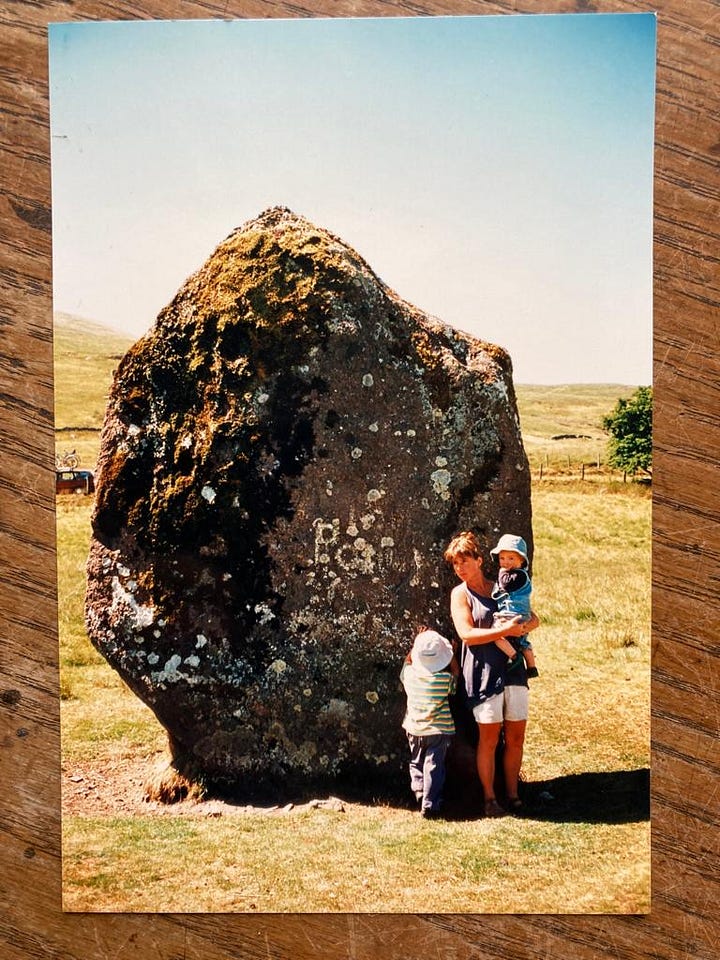

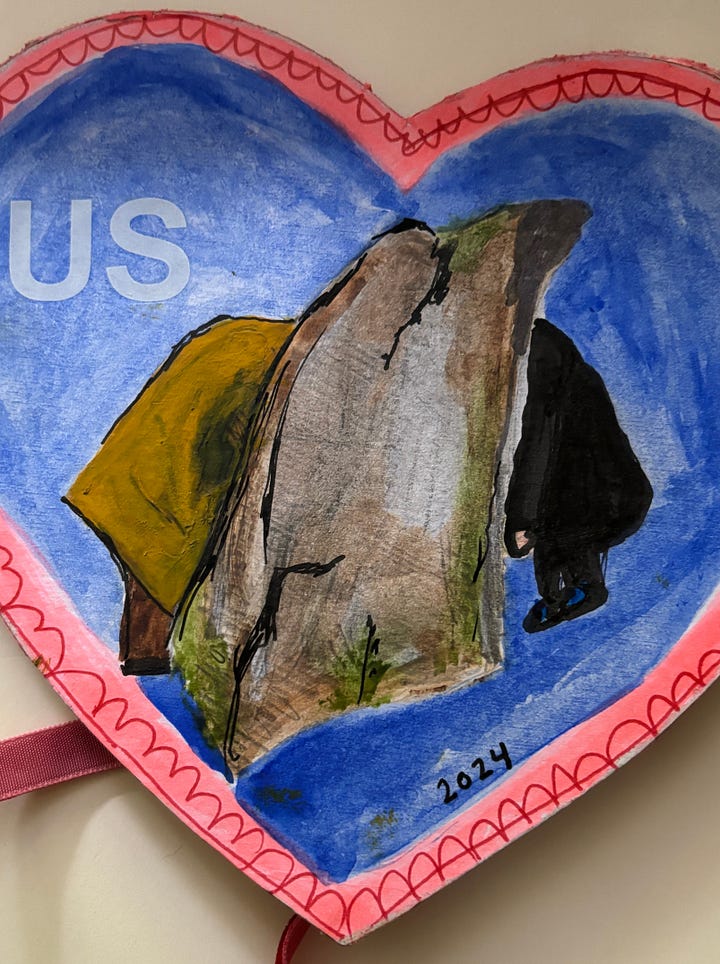

The time I touched Maen Ilia as a 5 year old on a road trip through Wales with my parents and baby brother. The thrill of coming upon the Nine Maidens on Dartmoor with Ward, the slumped ladies frozen in time for dancing on the sabbath peeking through the mist. The astounding beauty of the amphitheatre-like ringed horizon surrounding the still-gloriously-exposed and vulvic Arbor Lowe. The faces at Avebury. The golden buttercups carpeting Stanton Drew, the cows rubbing their chins on the meteor-like stones. The singing stone into which Flannery and I submerged ourselves, just beneath the modern stone circle with aspects of motorway, gothic cemetery, car dealership, and empty new build estate.

The types of people that you encounter at these places: the well-equipped walkers with coloured goretex raincoats and slim backpacks; the photographer with a camera bag searching for the best angle; the pilgrim, offering a shard of quartz and making connection with ancestors in still, silent contemplation; the curious day tripper, trying to get a sense of the history of this island beyond the country estates and pervasive colonial undertones.

//

It must be said: these overtones can be found in folklore circles as well. There is important work to be done in making these sites more accessible, culturally and physically; to decolonising the stones, reclaiming them from traditionalist, patriarchal, and white supremacist interpretations of British history and folklore. The work of Nicolette Clara Iles stands out as important in this respect.

//

Beyond my direct interactions with these places, there is the art that people have made about Stone Circles and their sister sites. The Avebury Letters, Daniel & Clara's ongoing mail-art series comprising stories regaled by the stones at Avebury. The hypnotic drone of the hurdy gurdy at the Gurdy Stone, and Rachel Poulton's photographs of the modern-menhir shrouded in yellow smoke. Derek Jarman's Journey to Avebury, Stanley Schtinter's modern remake, and NKISI's accompanying album. The people who make this art are embedded in their work, and their work is an extension of who they are and their relationship to these places.

And then there is the imagined purpose of the stone circle. Sites of ritualistic gathering where collective rapture was sought by pilgrims and travellers from across the world; where feasts and orgiastic ecstasies took place on those threshold dates that now form the pagan Wheel of the Year; where offerings were made and votives deposited for gods of the sky and of the earth; where stories were retold and invented, songs sung and forgotten, lives begun and ended.

The erotic pull exerted upon my body by any given Thing - object, person, place, idea, theory - can as much be a function of the various social associations that I stain or gild the thing with as it can be as a result of the felt aesthetic attraction that the Thing elicits in my body.

The degree to which a Thing is attractive according to its social associations, or according to its aesthetic attraction varies. Sometimes I will encounter something so beautiful that it seems even without context, I would experience erotic attraction to it. Conversely, I can find something aesthetically unattractive, but still feel an erotic pull as a result of the social associations that I have imbued it with over time. People that I love and feel a deep attraction to will be able to imbue nearly any object that they love with an erotic force that draws me towards it.

//

I'm going to build a stone circle of flint.

It is not just a circle made out of a significant local stone though. It’s circumference grows larger; it contain every other stone circle. Even wider, gaping now; it contains all the associations that I have accumulated as subconscious sediment; the lives of many, imagined and real, and their work, their creations, their relationships to each other and to me. Most of all, it contains my love for all of these people.

If you enjoy reading this newsletter, consider a paid subscription. All posts will remain free to read, so you don’t get anything for it except the satisfaction of supporting something you like. It would be very gratefully received! If you sign up in May you can get 50% a paid subscription forever.

With love and solidarity